Cedars cause trouble for ranchers and upland birds alike

By: Casey Sill

You have to admire the resiliency of the eastern red cedar, though there’s not much else to love about it.

The eastern red cedar is what’s known as a “pioneer species” — a tree or plant that will readily inhabit recently disturbed, nutrient poor, or otherwise uninviting land. Basically, they’ll grow damn near anywhere.

Rocky ground, sandy ground, steep slopes, full sun, dry land, take your pick. As the name suggests, they’re native to the eastern half of North America, and can be found from Maine to Florida, and from the Atlantic coast to Texas.

Their rapid expansion is most notable in the Great Plains — South Dakota, Nebraska, Kansas and Oklahoma specifically — where cedars can eat up large swaths of prairie and ranch land in a short period of time. An army of encroaching cedars leads to all kinds of problems, both for landowners and the grassland bird species that call these areas home.

The heavy canopy cover created by cedars deteriorates the health of grassland ecosystems, which has a negative affect on nesting populations of greater prairie chickens and many other bird species. The reduced quality of grasses also impacts the grazing ability of cattle ranchers.

“It’s very mutually beneficial to remove these trees,” said Ryan Lodge, Pheasants Forever’s working lands coordinator. “It creates more grassland for ranchers, and also provides healthy nesting habitat for these grassland dependent bird species.”

The eastern Sandhills of Nebraska are at the heart of the cedar removal zone. In recent years their work has been helped immensely by grants from the National Fish and Wildlife Federation, the Northern Great Plains Program and the Nebraska Environmental Trust Funds. These grants have lead to significant habitat improvements across the state, a large part of which is focused on red cedar removal.

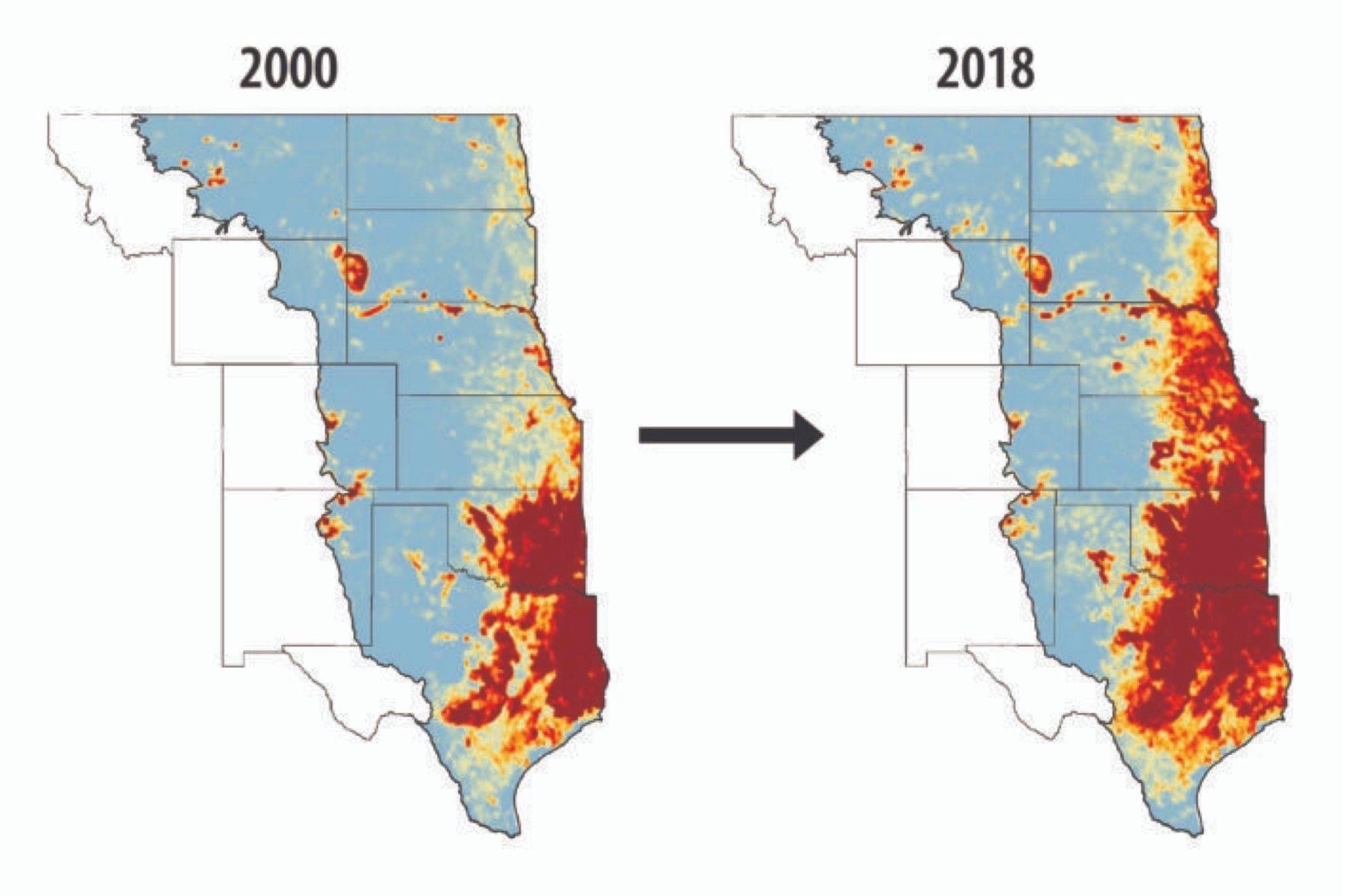

Eastern Red Cedar expansion in the Great Plains between 2000-2018.

Eastern Red Cedar expansion in the Great Plains between 2000-2018.

The most recent grant will help restore 50,000 acres of habitat by working with private landowners to remove invasive trees, reintroduce historic burning regimes, reseed native grassland species and follow best management practices for grazing.

“Altogether we’re probably over $1.5 million received in grant funding since 2018,” said Nebraska state coordinator Kelsi Wehrman. “These partnerships result in high quality, tangible changes on the landscape through things like cedar removal, as well as through the purchase of prescribed fire equipment, workshops and training sessions.”

Prescribed fire is one of the most dominant forms of red cedar control in the Great Plains. Historically speaking, as industrialization moved west and native prairie was cut with roads, towns and fences, natural wildfires became less common. Lack of fire creates ample opportunity for red cedars to expand uninhibited, but reestablishing regular controlled burns helps dramatically to offset their growth.

“We’re using mechanical removal in conjunction with prescribed fire, which is the best method to remove the trees, but also prevent future seeding,” said Tanner Swank, a Quail Forever coordinating biologist in Oklahoma. “Each one of these trees can distribute up to 1.5 million seeds, and if you just do mechanical clearing and don’t burn, you’ll see seedlings return in two years.”

As you move south, the primary concern of red cedar infestation shifts from grassland health to wildfire prevention. This is especially true in Oklahoma, one of the most fire prone areas of the country, where dry conditions and an abundance of fuel sources can lead to devastating fires.

“We’ve seen it out here all too many times,” Swank said. “With the big fires as of late, starting in 2016 with the Anderson Creek fire, people see how volatile those cedar trees are. They’re basically incendiary bombs dotting an area where fires are already hard to fight.”

In addition to being a fuel source, cedars also consume massive amounts of water, which can worsen drought conditions in an already dry area. Just one acre of eastern red cedars can consume as much as 55,000 gallons of water per year from the surrounding area, according to the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service.

“There’s a lot of springs out in this area and a lot of them have either reduced flow capacity or have just stopped flowing altogether, in part because of cedar trees,” Swank said. “Each tree can consume 25 or 30 gallons a day. So when you get a ravine with several hundred cedar trees in it that’ve been there for 50 plus years, it doesn’t take a rocket scientist to figure out where your water is going.”

During removal, trees are normally cut down and stacked into piles or dropped into the canyons that are so common in the area, then burn teams come in and finish the job with fire. It only takes 150 degrees internal temperature to kill a cedar tree, which makes fire all the more effective for any trees left standing.

“Even if a fire doesn’t “crown out” (reach the tops of the trees as it moves), you can roast them,” Swank said. “And kill them with heat alone.”

Swank and his team in Oklahoma are currently implementing large-scale fires to clear some of the last remaining cedar strongholds in the northwest portion of the state. The burn areas for these projects are significant, up to two square miles in some cases. Fire of that size takes a massive amount of collaboration, and Quail Forever is partnering with the Natural Resources Conservation Service, the US Fish and Wildlife, the Oklahoma Department of Wildlife Conservation and local volunteer burn associations to accomplish the projects.

“These burns are not for the faint of heart, but it’s what we’ve started to specialize in now because it’s what needs to be done,” Swank said. “If we don’t burn and restore these acres under our terms, Mother Nature is going to do it for us — and you don’t want that to happen.”

Casey Sill is the public relations specialist at the Pheasants Forever national headquarters in St. Paul, Minn. He can be reached at csill@pheasantsforever.org